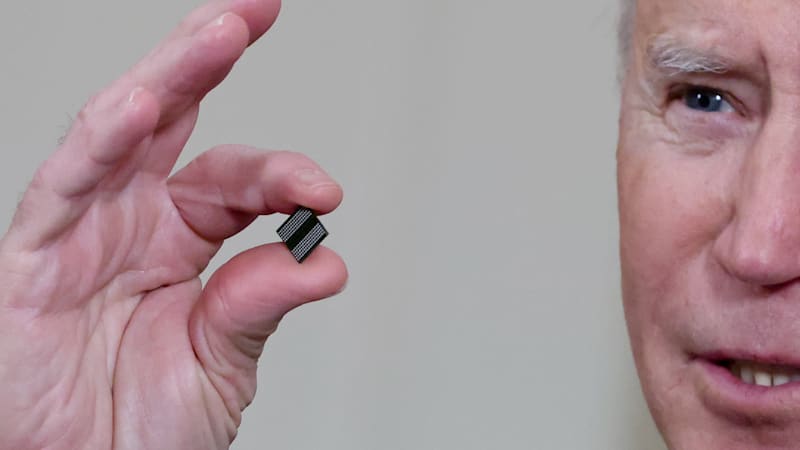

When President Joe Biden stood by a lectern on Wednesday with a microchip and pledged to support $ 37 billion in federal subsidies for US semiconductor manufacturing, it marked a political breakthrough that happened much faster than industry insiders expected.

For years, chip industry executives and US government officials have been concerned about the slow relocation of costly chip factories to Taiwan and Korea. While major American companies such as Qualcomm and Nvidia dominate their field, they depend on factories abroad to build the chips they design.

As tensions with China mounted last year, US lawmakers approved manufacturing subsidies as part of an annual military spending bill, fearing that relying on foreign factories for advanced chips posed national security risks. Still, funding for the grants was not guaranteed.

Then came the auto chip crunch. Ford said a shortage of chips could cut production in the first quarter by a fifth and General Motors would cut production in North America.

“It conveys very clearly the message that the semiconductor is truly a critical component in many of the end products that we take for granted,” said Mike Rosa, head of strategic and technical marketing for a group within semiconductor manufacturer Applied Materials Inc. sells tools to auto chip factories.

Within weeks, automakers joined chip makers calling for grants for chip factories, and US Senate Leader Chuck Schumer and President Biden both pledged to fight for funding.

Industry supporters now want to be part of a package of anti-China legislation that Schumer hopes to bring to the Senate this spring. Still, they all agree that it will do little to fix the instant auto chip problem.

The headlines about stationary car factories resonated with the public who had in the past rejected abstract warnings, said Jim Lewis, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Legislators, already worried that a promised infrastructure law won’t be realized this year, decided to push for a quick fix.

“Nobody wants to be seen as being soft on China. Nobody wants to tell the Ford workers in their district, ‘Sorry, I can’t help it,’” said Lewis. “It was one of those times when everything was aligned.”

The package includes matching funding for state and local chip factories, a facility that is likely to increase competition between states, including Texas and Arizona, to accommodate large new chip factories that could cost as much as $ 20 billion.

The subsidies could benefit a factory in Arizona proposed by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co and one in Texas being looked at by Samsung Electronics, even if those factories would focus on high-end chips for smartphones and laptops, rather than on simpler car chips. And those factories wouldn’t come into operation until 2023 or 2024, according to plans announced by the companies, the world’s two largest chip makers.

In the longer term, many US companies will also benefit from this. All chip makers building factories will buy many tools from US companies such as Applied, Lam Research and KLA Corp.

Intel, Micron Technology Inc and GlobalFoundries – which already have US factory networks – are also likely to benefit.

Smaller, specialized chip factories could also benefit from this.

“The recent chip shortage in the automotive industry has underscored the need to strengthen the microelectronics supply chain in the US,” said Thomas Sonderman, CEO of SkyWater Technology, a Minnesota-based chip maker that makes automotive and defense chips. “SkyWater is uniquely positioned due to our differentiated business model and status as a US and US operated pure play semiconductor contract manufacturer.”

Even with subsidies, US companies will still have to compete with low-cost Asian suppliers in the long run, and immediate auto chip problems are likely to continue.

Surya Iyer, a vice president at Minnesota-based Polar Semiconductor, which makes chips for automakers, said his plant is fully booked and is speeding up some orders and slowing others down to best meet the needs of automakers.

“We expect this level of demand to continue for at least the next 12 months, maybe even longer,” he said.